Is death an acquired trait? We like to think of death as unavoidable. We believe that all things must die. It makes our own mortality easier to bear. Yet single-celled life forms don’t necessarily ever die. They can beat the odds and indeed every surviving amoeba on earth has been alive billions of years.

So maybe death is not inevitable and is just an evolutionary trait. Death may be a competitive advantage devised by multi-celled life forms. That seems pretty counter intuitive. After all, the purpose of life is to live, right? Death must be life’s unavoidable antagonist, an environmental villain that life strives to overcome, that evolution or intellect may one day conquer. But what if death is something that our distant ancestors created, a necessary evil that helped them better compete with immortal species? What if death is not even a necessary evil, but beneficial?

What is a Death Gene?

If it exists, the death gene would be DNA programming that limits our life span. Something that makes a species’ dying much more predicable than random accidents otherwise would. Evidence of this is all around us. Most insect species live a season at most. Dogs are good for ten to fifteen years. We live 60 to 100 years (though probably without modern medicine, 40 to 70 years is closer to our natural genetic programming). Some turtles live much longer than we do even without medical technology. Some species of trees live many hundreds of years and there are redwoods over 2,000 years old.

Still, maybe environmental or anatomical constraints determine life spans? After all, most insects are not capable of living through a cold winter. Maybe it is the seasons that kill them and not their own genetic programming. But what is so different between dogs and humans that humans deserve to live five times longer? Nothing that I can see. We just do because our DNA tells us to.

About five years ago, scientists in Scotland found a genetic sequence on our fourth chromosome that may stop cells from “living and dividing infinitely” after their allotted life span. Such a gene is thought to be crucial in controlling cancer. “Cancer cells have various defects that keep them alive and allow them to divide well beyond their allotted life span.” Cancer may be caused by a defect in our death gene. Without cellular death, complex multi-celled life cannot exist.

Evolution Speeds Up

As far as we know, life appeared soon after the Earth formed about four billion years ago. During the next three and a half billion years, cells grew more complex internally and discovered photosynthesis (which incidentally filled the atmosphere with oxygen, the most toxic pollution of all time). But change was slow and life remained single-celled and tiny. Then just over half a billion years ago, multi-celled life appeared and evolved very quickly in complexity and size.

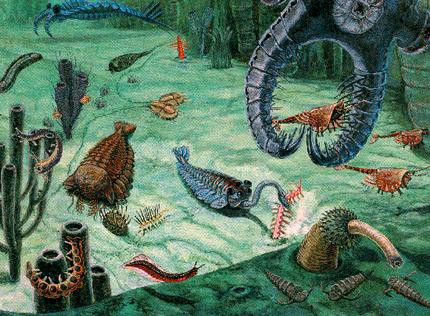

The Cambrian explosion is paleontologists’ term for fossils of diverse complex animals that appeared rather abruptly around 530 million years ago. Precursors of modern mollusks seem to have appeared first, followed by arthropods and other phyla, precursors to all of modern fauna. About 10 million years of evolution seems to have produced more change than all the preceding eons, hundreds of times longer.

Why did diversity explode just then? One theory is that it didn’t. Maybe life had become complex much earlier but was just too small to see in our fossil record. Fossils are made of rock and rock is made of crystals. A crystal is the minimum “pixel” size of a fossil image. And of course soft bodied animals would not fossilize well. And there is some disputed fossil evidence of multi-celled life before the Cambrian, though not much before 600 million years ago.

Maybe Death Helps Life to Compete

Still, the consensus seems to be that evolution was somehow accelerated during a fairly brief Cambrian epoch, just over 500 million years ago. To me, it seems likely that this “explosion” was due to something newly evolved, some competitive mechanism that allowed life to both spread and change more rapidly than ever before. The jump to multi-celled animals must have been a high hurdle for evolution, one that probably needed a catalyst. Once evolution discovered that catalyst, diversity exploded. Then competition from all those newly evolved phyla must have quickly throttled back the rate of change.

The catalyst may have been genetically programmed death. Independent single cells die, but they don’t have to. Those individuals that survive effectively live forever. Contrast that to us. No one has probably ever lived longer than about 120 years. And that implies that none of our cells has either. Except for the germ cells, the eggs and sperm that keep our DNA alive between generations. But germ cells don’t really count except for their DNA.

How would death help life to compete? It might just be a side effect of the need for cells to cooperate in a multi-celled organism. Fundamentally designed for independent existence but harnessed together into a cooperative whole, cells probably require death as a throttle. Cancer is the design flaw that results when you build life out of individual cells. Genetically programmed death is the tool that (mostly) controls it.

Possibly our DNA has acquired built-in counters at the end of our chromosomes that are snipped off with each reproduction. When the counter reaches zero, reproduction stops and death is inevitable. Without this counter (and probably other throttles as well), cancers occur and bodily tissues stop cooperating. Multi-celled life uses death to harness independent cells that are still inclined to compete with each other.

But death probably serves life in another important way. Frequent death should speed up evolution. It forces more generations in a shorter period than natural environmental hazards might. With more generations, we have more chances to evolve random but beneficial new traits.

When I first heard of the Cambrian explosion, I naturally wondered what could speed up evolution so dramatically? I believe death is the likely answer. And if evolution did suddenly speed up, that implies that death as a genetic trait might have first evolved just prior to the explosion of multi-celled life forms half a billion years ago. That makes death a relatively new idea, an advanced concept that took billions of years to evolve.

Consequences

Programmed death has something in common with sex. Both are fundamental to complex life. Nearly all higher plants and animals use them and so the evidence is strong that they are highly useful competitive tools. Sure, sex is pleasant and death is not. But when you think about it, both sex and death are unselfish acts that inconvenience the individual for the benefit of the species (or at least its DNA). As much as we enjoy sex, one wonders whether twenty years of parental servitude is a cost worth five minutes of pleasure. Sex and its consequences are enjoyable because rewards work better than punishment and our genes know that. But death allows for no reward. I’m sure our DNA would reward the act of death if needed. But nature needs nothing further of us afterward and so no reward mechanism has evolved.

DNA is really the soul of life. And DNA remains immortal, at least from our limited perspective. Our mortal selves and even our mortal thoughts and self-awareness are really just expendable tools of a higher life form: our genes. Maybe there really is a god. Maybe life’s DNA is a scientifically verifiable deity. A god that does indeed hold our lives and our destiny in its hands. Like our parents, we owe everything we are to this god. But like our parents, we are often in conflict with its goals. There is certainly conflict in this death thing. Our DNA wants it and we don’t. Godlike DNA wins.

I’ve argued that death may be genetically programmed rather than inevitable. That death allows our DNA patterns to more successfully survive and evolve. Of course, death is not in our personal interest, at least individually. And it seems to me that the existence of death causes a lot of unforseen social consequences. After all, society is a mechanism that allows otherwise competitive individuals to cooperate. But who cares about cooperation when we are all dead in the long run? Genocide, wars, murder and all of the other human-created ills we face would not be in our best interest if we planned on living forever. But being mortal, short term accomplishments are all that really matter.

Bad for the individual and dangerous for society, should we eliminate death if we could? Probably not, unfortunately. Destructive as it is, death is also the soul of human motivation. What would we ever strive for without it?